Sifting fake news from reality in the social media age is a challenge for us all. Misinformation, untruths and conspiracy theories spreading through social media are disrupting society as we’ve seen in the US election, vaccine roll-outs and the war in Ukraine.

Sorting facts from gossip and innuendo was traditionally the role of journalists but erosion of conventional news outlets means journalists are thin on the ground and being substituted by spin doctors, social media influencers and activists.

I’ve always wondered about figures attributing large amounts of water and chemicals to the production of cotton, and my scientific training made me wary of sharing these in my slow clothing advocacy work. I know the Australian industry has introduced water efficiency measures and some regions grow dryland (non-irrigated) cotton. Additionally, Australian growers use integrated pest management along with seed that has been genetically modified to resist insect attack.

The fashion industry is full of misinformation. People are fed the latest trends and treated like mushrooms, there’s endless greenwashing and a lack of transparency exacerbated by data kept behind paywalls. There’s even a ratings systems which ranks synthetic fibres like polyester that sheds microplastic particles as being more sustainable than natural fibres. How can that be? Polyester is plastic. It might use less water that cotton but is created from fossil fuel and its full polluting impact needs to be factored in.

It is helpful to see a new report Cotton: a case study in misinformation developed by the Transformers Foundation which represent the denim supply chain with the stated goal to help suppliers share their expertise and opinion on industry threats and solutions, brands and retailers to transform their jeans from a commodity into unique and valuable fashion, and consumers to choose the most environmentally-sound denim products and avoid greenwashing. You can download the report at this link https://www.transformersfoundation.org/cotton-report-2021 or read some direct quotes below.

“Fashion has a major misinformation problem. Half-truths, out-of-date information and shocking statistics stripped of context are widely circulated, from the notion that fashion is the second-most polluting industry to the idea that cotton is thirsty or that it consumes 25 percent of the world’s insecticides. While there have been attempts to debunk fashion misinformation, we have not taken the problem seriously enough. Fashion misinformation is part of the same society-wide information disorder destabilising democracies and undermining public trust.

“This report aims to take a new approach, using the cotton industry as a lens through which to tackle misinformation. Most of the common claims about the cotton industry are inaccurate or highly misleading (from the idea that cotton is water-thirsty to the notion that it takes 20,000 litres of water to make a T-shirt and a pair of jeans). It is an ideal place to begin to unpack how misinformation operates.

“Fashion misinformation is complicit in the same systems of misinformation breaking down public trust in our institutions and our trust in one another. Misinformation’s impacts are becoming more catastrophic, linked to public inaction around climate change, the questioning of the 2020 US election results, the rise of authoritarianism, and the threat to democracy worldwide. Sharing half-truths about how much water cotton consumes or the fashion industry pollutes might seem innocent by comparison, but it is all part of the same information disorder with troubling shared consequences.

“The stakes couldn’t be higher. The $2.5 trillion fashion industry’s environmental impact grows every year, with only a temporary slowdown during the pandemic. It is crucial for industries and society to understand the best available data and context on the environmental, social and economic impact of different fibres and systems within fashion, so that best practices can be developed and implemented, industries can make informed choices, and farmers and other suppliers and makers can be rewarded for and incentivised to operate using more responsible practices that drive more positive impacts.”

“Digital tools and social media networks make it possible to instantaneously share information that can quickly travel across the Internet. Social media and more precisely the amplification of fake news stories on social networks are picked up and released through mainstream media. This pipeline has overpowered newspapers as a main way that new stories are discovered, and much of this information is moving too quickly to be vetted. Exaggerated claims and sensationalism (and algorithms that prioritise them) drive more likes, garner more followers, and reward users for spreading misinformation. But it’s not just social media that’s to blame.

“Misinformation is also spread by private actors, namely companies who use deceptive marketing to describe their products or services as more sustainable than the competition or compared to an earlier iteration of their own business. This is known as greenwashing, and it’s a massive problem in fashion. In 2020, the European Commission analyzed 344 consumer product claims made online about sustainability, a quarter of which were made about clothing, fabric, and shoes. Almost half of all claims analyzed were flagged as possibly deceptive.”

The report indicates fashion as an industry has not been taken seriously and does not have independent or non-corporate groups scrutinising and analysing the sector. It has historically been dominated by creatives, and needs to build technical and scientific expertise.

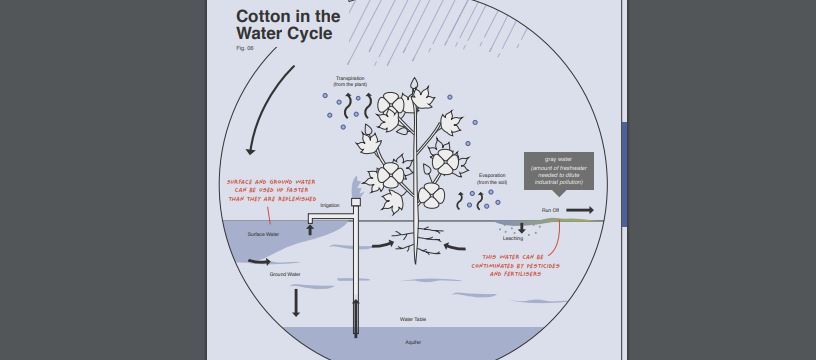

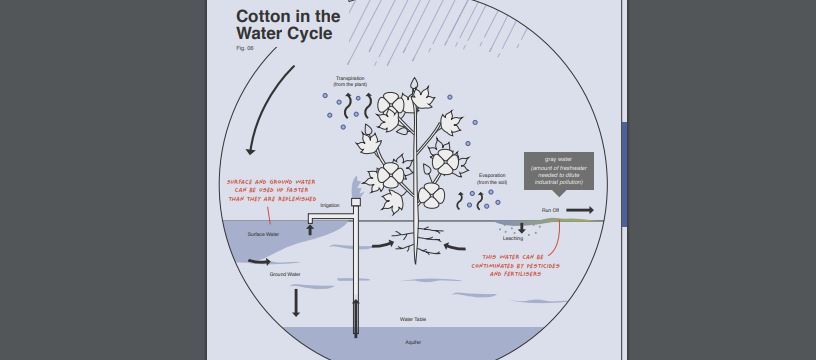

In the end, there is no single definitive figure for water usage due to the wide range of growing countries and situations. This comment, from page 72 of the report, explains the place of water in our ecosystem: Water is borrowed from the global water cycle. It can be moved, polluted, change forms, or returned from where it came, but it can’t be ‘used up.’

The key to sustainability is wearing clothes until they wear out. When we extend the life of our clothes, we minimize the impact of the original inputs used to produce them.