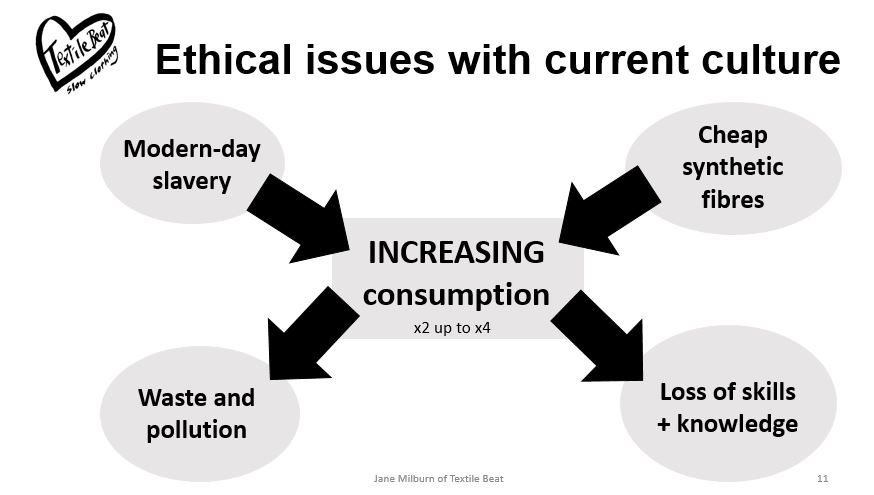

Individuals can create change through actions and choices. When we become conscious of social and ecological impacts of what we wear, we can choose to make different decisions. Jane Milburn noticed fashion waste in 2011 and began exploring ethical issues associated with contemporary clothing culture in developed nations. These are documented in her book Slow Clothing: finding meaning in what we wear, which makes a compelling case for why we need to change the way we dress, to live lightly on Earth through every day practice. The diagram below shows the interlinked factors of increasing consumption driven by modern-day slavery and changing fibres, compounded by waste and pollution (in production and consumption), and the loss of knowledge and skills to make or repair our own clothes.

Modern-day slavery

Global supply chains are highly efficient at producing clothes (electronics, stuff etc) cheaply but since the Rana Plaza factory collapse, we now know this is on the back of modern-day slavery. Australia has passed Modern Slavery Bill in 2018 but businesses are not compelled to comply. As consumers, how we spend our money makes a difference. Seek out accredited products, from companies that can demonstrate they are paying living wages.

Changing fibres

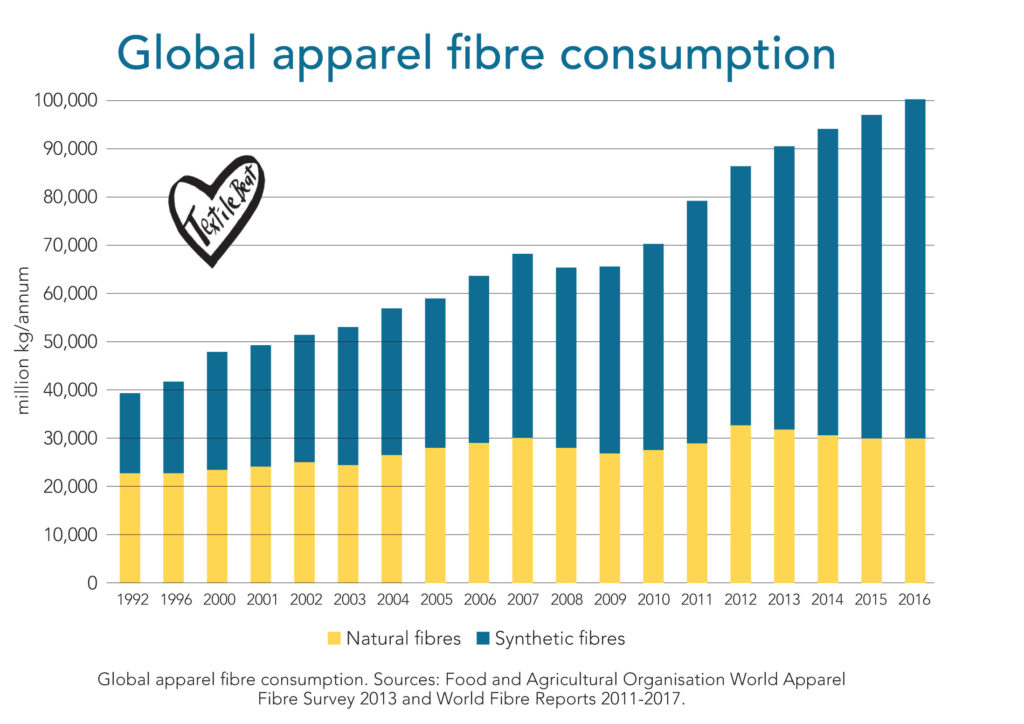

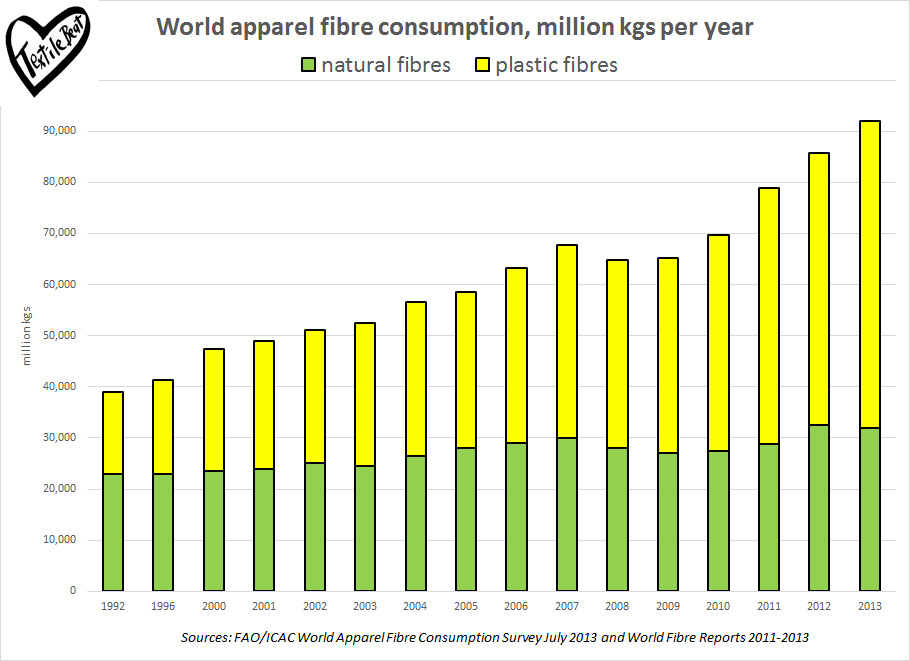

Two thirds of new clothing is made from synthetic fibres derived from petroleum. These are effectively plastic and may never breakdown. Research has shown they shed microplastic particles into the ecosystem with every wash. Microplastic is showing up in seafood we eat, water we drink and air we breathe. The human health effects are still under study, although it is known these fibres carry chemical endocrine disruptors that influence hormone functions and chronic disease. A recent report from the International Union of Concern for Nature confirmed primary microplastics in the oceans predominantly comes from machine-washed synthetic textiles. The graph below shows how the volume of apparel fibre produced/consumed has increased over time, and how the proportion of synthetic fibres has escalated in the past decade.

Increasing consumption

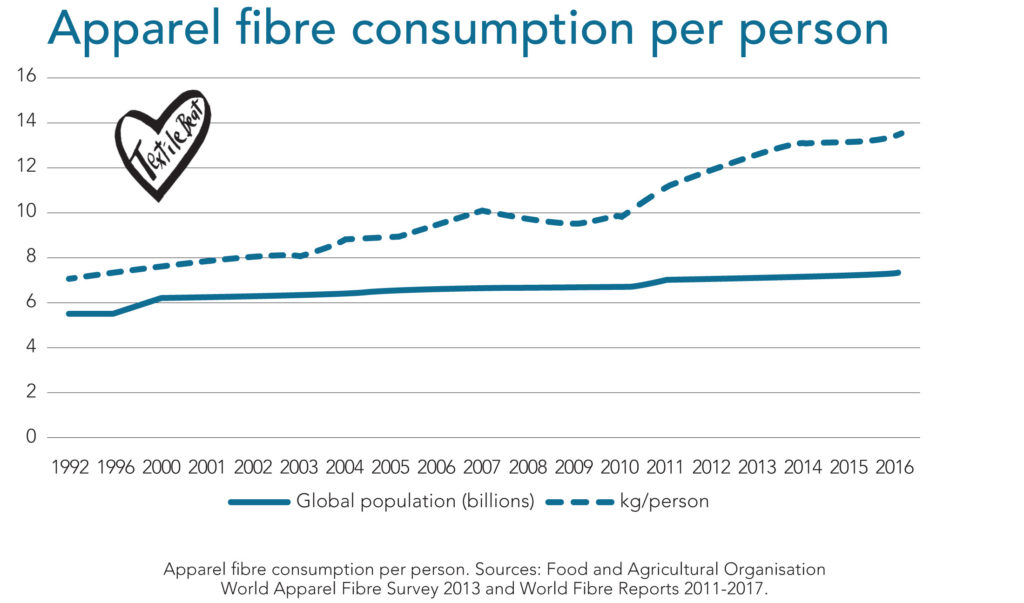

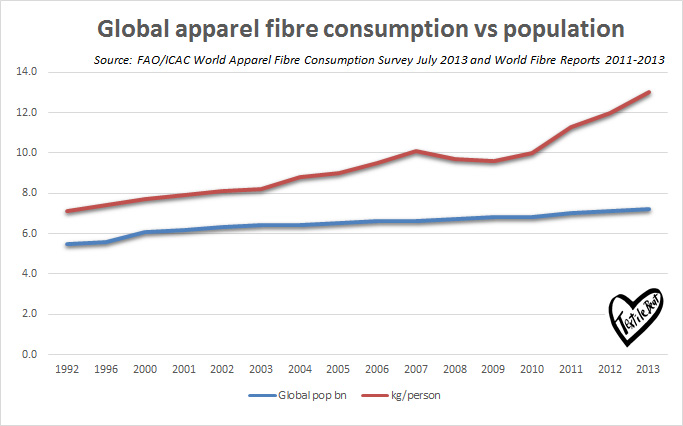

Individual clothing consumption has doubled, based on the global average, from 7kg two decades ago to nearly 14kg now, according to data compiled below from Food and Agriculture Organisation World Apparel Fibre Consumption Survey extrapolated with annual World Fibre Reports. There are still only 365 days in the year, yet per person consumption is predicted to rise further. We are buying a lot more than we need.

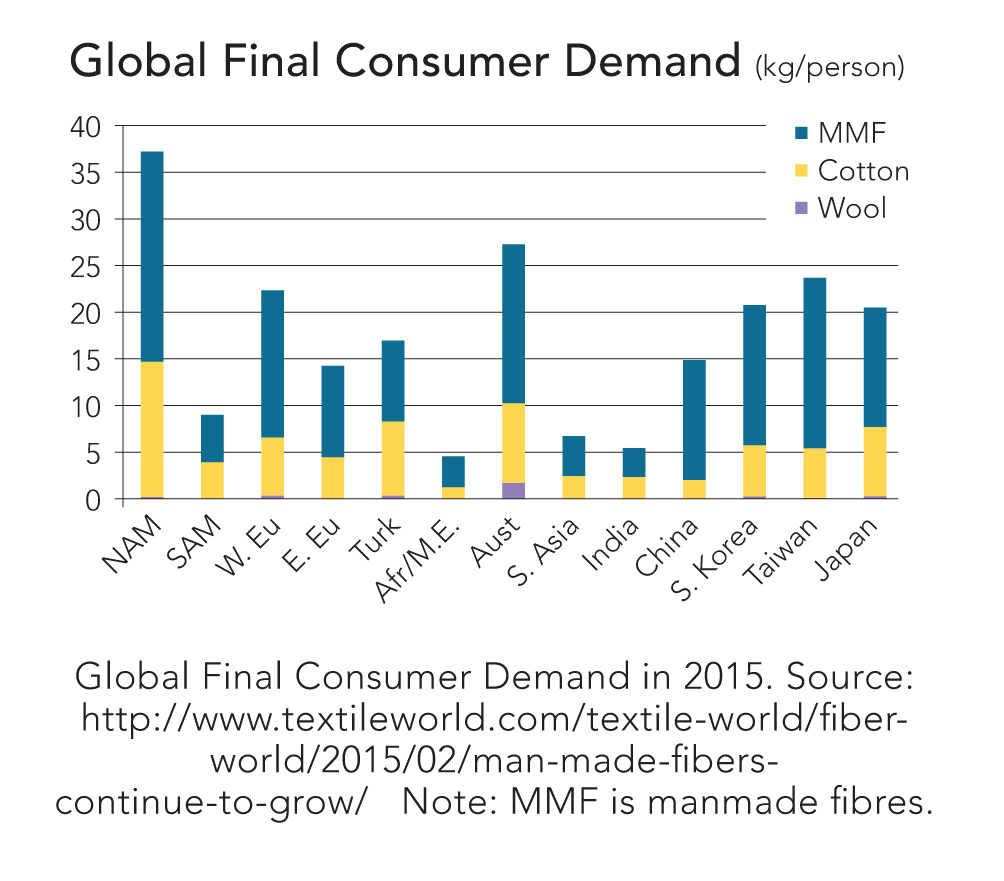

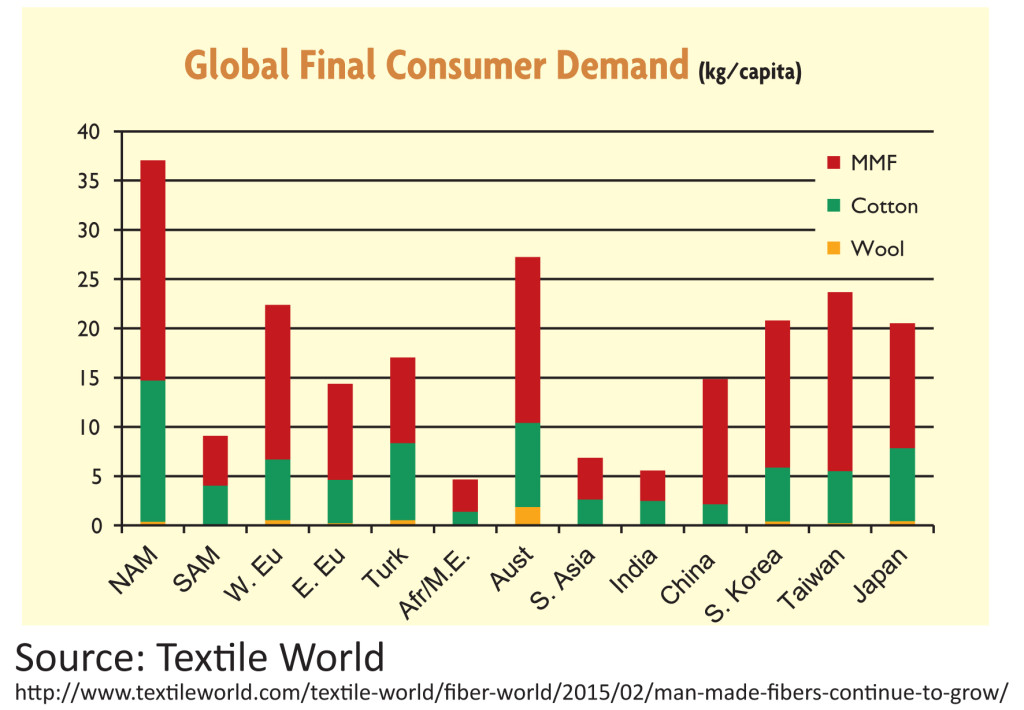

Australasians are the second-largest consumers of new textiles, averaging 27kg each, after north Americans (37kg each), according to 2015 information from Textile World (see graph below). This is well ahead of Taiwanese (23kg each), Western Europeans (22kg), South Koreans (21kg) and Japanese (20kg). These figures contrast starkly with less affluent nations of Africa and India where the average per person is only 5kg.

Waste and pollution

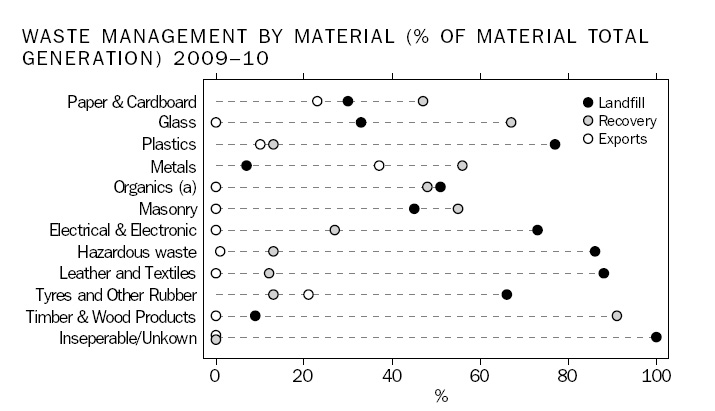

According to Australian Bureau of Statistics 2013 figures, 500 million kg of leather and textiles are discarded to landfill each year. That equates to 23kg of leather and textiles (including carpets) for every Australian. The ABC’s War on Waste program in 2017 reported 6000kg of clothing and textiles go to landfill every 10 minutes in Australia. Charities have traditionally been the clearing house for unwanted clothes, with 60% sold as clothing (most of that into the global secondhand trade), 15% as industrial rags and 25% to landfill. According to the National Association of Charitable Recycling Organisations (NACRO), Australia exported 70,000 tonnes of secondhand clothing in 2012 (sold for $1/kg) and that increased to 88,000 tonnes in 2016 – an increase of 25% in four years, reflecting the upward trajectory in new clothing during the same period. The global secondhand market is not a long-term solution. We need to buy less, and wear it for longer if we want to dress with conscience and minimise our material footprint on the world.

Loss of skills and knowledge

Sewing skills, and knowledge and understanding of how clothes are made, have diminished to the point where, across the population, we are now physically dependent on the supply chain and may not even know the basics of mending. We believe sewing and stitching are life skills, just like cooking and baking. Life skills enable us to provide for ourselves. This is the essence of what we call slow clothing. It matters because until we make something for ourselves to wear, we cannot appreciate the resources, time and skill that go into the clothes we buy. This leads to a spiral of excess, waste and exploitation, outlined above.

Returning to a more hands-on approach has rewards. Here are 10 ways that stitching enhances life:

- expands choice – you are not restricted to what you can find ready made

- provides agency – everyone’s body is different, it is great to be able to suit yourself

- offers challenge – how can I make this work?

- enables repair – extend life of favourite garments

- gives a sense of accomplishment – gain real achievement from completing tasks and details

- encourages creativity – grown-up play

- connects us with clothing – we put energy and care into a garment we make or repair for ourselves

- creates mindful immersion – through soothing repetitive actions

- saves unnecessary expenditure

- reduces waste, which is increasingly important in a finite and climate-changed world

Above, updated December 2018. Earlier version remains below.

……..

Increasing consumption

In the past two decades, world apparel fibre consumption doubled (increased 100%) while global population increased by 30%. Individual annual average consumption was 7kg in 1992, and increased to 13kg/person by 2013. The graph below complied by Textile Beat using data from various sources, show the comparison between global population increase (blue line) and individual textile consumption (red line).

The graph below shows Australians buy 27 kg of textiles annually, making them the second-largest consumers of new textiles after north Americans who buy 37kg each, and ahead of Western Europeans at 22kg while consumption in Africa, the Middle East and India averages just 5 kg per person. (Graph from Textile World, 2015)

Change in fibres

Two-thirds of new clothing is made of synthetic fibres, which are derived from petroleum. Research in 2011 by ecologist Dr Mark Browne found thousands of microplastic particles are being shed from synthetic clothing with every wash. Synthetic fibres are plastic and take decades to decay in landfill. Natural fibres are biodegradable.

Modern-day slavery

The dark underbelly of fast fashion and cheap clothing was exposed when the Rana Plaza factory collapsed in April 2013, injuring thousands and killing 1133 people. We are part of Fashion Revolution and Fashion Revolution Day on April 24 which honours those workers and encourages us to ask #whomakemyclothes and Be Curious, Find Out, Do Something.

Waste

- Nearly 1/3 of clothing goes prematurely to landfill in the UK – and similarly in Australia.

- Australia annually ships 70 million kilograms of cast-off clothing to developing nations, sold for $1/kg. While this has some positives, it is a way of exporting our waste.

- Many people have bulging wardrobes, with many garments rarely worn.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics figures indicate 500,000 tonnes of leather and textiles are discarded each year and only a fraction of this is recovered through charitable recycling.

Loss of skills and knowledge

- There is a lack of respect for the time and resources involved in making clothing

- The loss of simple sewing skills means an inability to repair, or replace buttons

- This lack of knowledge and skills creates dependency and a lack of autonomy

Textile Beat’s philosophy aligns with The Earth Charter which recognises our global environment has finite resources. It specifically relates to ecological integrity as outlined in Principle 7a: Reduce, reuse, recycle the materials used in production and consumption systems. It also aligns with the United Nations’ 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development goal to ensure sustainable consumption and production patterns.

Hello Jane. We are getting closer to initiating our ‘mending circle’ here at Rose Blossom Children childcare…will let you know when it is underway.

Sounds fabulous Vicky – teaching life skills for sustainability, well done.