Slow Clothing is the antithesis of fast fashion. It is a way of thinking about, choosing, and wearing clothes so they bring value, meaning and joy to every day. We have finite resources on Earth and careful use of those resources is required to sustain our individual and collective future. Slow Clothing is a holistic approach to dressing that enables self-empowerment and individual actions to enjoy clothes while minimising our material footprint. It manifests through ten simple actions and choices—think, natural, quality, local, few, care, make, revive, adapt and salvage. This post is an extract from Jane Milburn’s 2017 book Slow Clothing: finding meaning in what we wear.

Dressing is an everyday practice that defines and reflects our values. We are naturally attached to clothes on a physical, emotional, even spiritual level. We are particular about what we wear because we want to look good, feel comfortable, reflect an image and belong. Yet almost all our garments are now designed for us and we choose from ready-made options based on our age and stage of life, work, status and spending capacity. Unless we deliberately choose to step off the fast-fashion treadmill, we are trapped in a vortex with little thought beyond the next new outfit—without consideration for how we can engage our own creative expression, energy and skills.

Dressing is an everyday practice that defines and reflects our values. We are naturally attached to clothes on a physical, emotional, even spiritual level. We are particular about what we wear because we want to look good, feel comfortable, reflect an image and belong. Yet almost all our garments are now designed for us and we choose from ready-made options based on our age and stage of life, work, status and spending capacity. Unless we deliberately choose to step off the fast-fashion treadmill, we are trapped in a vortex with little thought beyond the next new outfit—without consideration for how we can engage our own creative expression, energy and skills.

The trillion dollar fashion industry is known to be highly polluting and has much room for improvement in its social and environmental performance. Global annual production is estimated at 100 billion garments[1] and this may accelerate with automation as sewbots begin producing one t-shirt every 22 seconds[2]. Two-thirds of new clothing is made from synthetic fibres derived from petroleum. These are effectively plastic and may never breakdown. Research has shown they shed microplastic particles into the ecosystem with every wash[3] and microplastic is appearing in 80 per cent of drinking water, the likely source being everyday abrasion of synthetic clothes, upholstery and carpets[4].

With the risk of dangerous climate change acknowledged by nations worldwide, we can all contribute by living lightly and engaging sustainable skills and strategies. Activities such as growing, caring, sharing, recycling, making, saving, upcycling and reusing may take a little more effort and commitment but it is the amalgamation of individual choices to slow consumption that can make a difference in the world. Conscious consumers are now looking beyond fashion and visual appearances to understanding that planetary health is at stake here—our clothing choices don’t just affect our own health, they affect the health of others and the health of our planet. While we cannot easily influence the way our clothing is made (unless we make it ourselves), we can become more informed and change the way we buy, use and discard it.

I stepped into this arena in 2012 as part of an active search for meaning. Through independent research and experiential learning, I sought to understand our clothing story in a context broader than fashion: a lifestyle context that includes everyday practice and individual creativity. I love natural fibres and noticed their presence in shops and on people was dwindling, while the overall volume of clothing was increasing and little of it was locally made. I went looking for information, made observations and considered the landscape. As we have gained by having cheap fast fashion on tap, we have lost the mindful, creative, resourceful benefits of doing things for ourselves. That’s one of the reasons why I undertook a social-change project in 2014 aimed at shifting thinking about the way clothing and textiles were consumed. The 365-day Sew it Again project demonstrated creative ways to upcycle clothing and empower individuals to tap into the most sustainable clothing is that which already exists in wardrobes and op shops. The project highlighted the value of sewing skills, encouraged a culture of thrift, and showed heartfelt concern. This was followed in 2016 by The Slow Clothing Project engaging like-minded makers across Australia.

What we wear impacts planetary health in ways that we are only beginning to understand. We endure marketing that attempts to convince us we need more to be fulfilled. Yet in the rush to own things for reasons of status and looks, we lose the opportunity to be mindful, resourceful and creative. Until we make something for ourselves to wear, we cannot fully appreciate the resources, time and skills that go into the clothes we buy.

We can step off the treadmill of constant and conspicuous consumption. People with a few hand-stitching skills can enjoy the independence of being able to make, upcycle, mend and adapt their garments. We can gain a sense of achievement and emotional attachment to our original work, while wearing garments that flatter our own body shape. Financial, social and psychological benefits flow from making sustainable and ethical clothing choices. Perhaps most importantly, we know no-one was exploited in the process.

Living non-extractively means relying overwhelmingly on resources that can be continuously regenerated: deriving our food and fibres from farming methods that protect soil fertility; our energy from methods that harness the ever-renewing strength of the sun, wind and waves; our metals from recycled and reused sources.

It is only in the past 100 years or so that abundance has created high-consumption lifestyles with a multitude of contrived and perceived needs that foster feelings of dissatisfaction with the status quo. If we reflect on our intangible health needs as outlined in Stephen Boyden’s The Biology of Civilisation (Boyden, 2004) we understand that including opportunities for creative behaviour and learning manual skills are important for our wellbeing. They bring a sense of personal involvement and purpose.

Living sustainably, based on the principles of permaculture and sufficiency, incorporates knowing how to grow and cook—and—make and mend. I know this because I live it. A homespun philosophy of valuing the old may be at odds with contemporary culture of forever more new, yet I pursue it in the belief that a circular approach will eventually bring these two perspectives together.

Slow Clothing values personal connection to garments through the stories and memories they hold. It considers the ethics and sustainability of our garments, their comfort and longevity, and our desire to be more engaged with the making process.

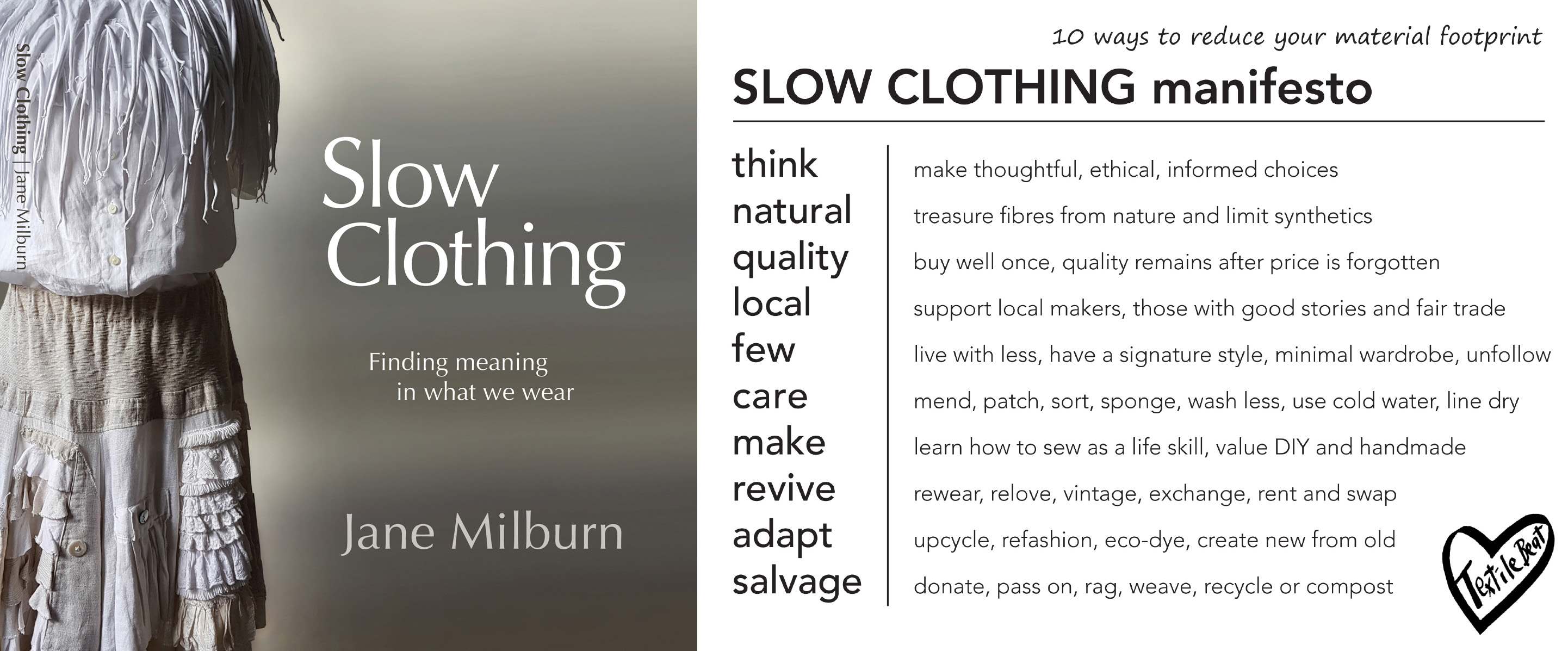

SLOW CLOTHING MANIFESTO

The Slow Clothing Manifesto is a framework of simple actions we can take as a process of thinking about how we can survive and thrive in a material world, and become more conscious of what we are wearing. It is not rocket science—these actions might once have been learned at school or passed on from one generation to the next.

The actions are: think, natural, quality, local, few, care, make, revive, adapt and salvage. The first five actions are about switching-on, while the second five get you more hands-on when you can make time.

Think

Reflect on the role clothes play in your life. Inform yourself about ethical certification and fair trade. Don’t be seduced into buying things just because they are on sale. Find more interesting things to do for recreation than shopping. Avoid going to places where you might be tempted to buy things you don’t need. Consider supporting social enterprise brands that produce clothes with social justice in mind. Select styles that have multiple uses and fastenings that are flexible with changing waistlines.

Before you open your wallet, let questions like these pass through your mind:

- Do I need it?

- Do I already have something like it?

- How often will I wear it?

- Will I wear it at least 30 times?

- Is it well made? Will it last 30 wears?

- Is it easy to care for?

- Does it need dry cleaning?

- Where is it made, and what from?

- Is it a responsible purchase?

Natural

My personal preference is to limit synthetics to products that require them, like swimwear and waterproof gear. Synthetic fibres are derived from petroleum and are a type of plastic. Synthetic fibres don’t breathe and research shows they are more likely to harbour bacteria and odour than natural fibres[5].

Reconstituted cellulose fibres—such as viscose, rayon, bamboo, lyocell and tencel—while manmade are derived from plants and wood and therefore more natural then synthetics. They have design advantages, are comfortable to wear and easy care. But there are concerns about chemicals used in their production. Check before you buy using resources such as the Good on You app.

Natural fibres tend to be more expensive and water-intensive to produce, therefore we should treasure them until they literally wear out! Cotton is the dominant natural fibre. Seek out sustainable and organic cotton where you can. Linen is one of the greenest fibres—just machine wash, shake, hang to dry and wear as is. I haven’t ironed linen for years—which saves energy and effort (although a short tumble dry gives a nice crinkle). Hemp is less readily available, but equally as green as linen (if not more so). Animal fibres like wool, alpaca, cashmere and silk are expensive and need a little extra care but will last a long time and wear well between washes.

While natural fibre manufacturing is limited in countries like Australia there are groups keen to change that. Full Circle Fibres for example is generating local cotton products.

Quality

Buy for the long-term. Quality remains long after the price is forgotten, as the old saying goes. Choose classic styles that will serve you well over time rather than fashion fads. Buy the best you can afford—buy things you love 100 per cent and wear them for a lifetime.

Do your due diligence before handing over cash. Look inside to check seams, finishes, fastenings and fabric type. Brand names may lead to inflated prices, so make sure there is real quality contained within any new purchase rather than smoke and mirrors. Seek out accredited companies that have stood the test of time, or use ethical fashion guides to inform your choices. Use department stores that have ethical sourcing policies, or online options that aggregate brands they trust. Choose brands that have a transparent environmental ethos that encourage recycling and reduced consumption by creating products designed to last a long time.

Local

Since the 2013 Rana Plaza tragedy revealed the globalisation race to the bottom on price, ethics and social justice, we have seen a desire to return to localisation. Buy local is a mantra ringing in Australia, in Britain, in America—not just with our clothing but with food and other aspects of life too. While only a fraction of clothing bought in developed nations is made onshore, there is growing interest in locally-made clothing and footwear. We can foster local industry by spending a little more on items that pay fair wages, and in turn support other local businesses. Many small manufacturers makers and upcyclers, selling online and at local markets, benefit from a commitment to buy local. You might also like to support local companies that make overseas yet know their supply chains and are Fairtrade-registered.

Few

Australians have the largest homes in the world followed by United States and Canada: I’m sure this equates to having the biggest wardrobes too! Minimalists confirm tiny homes and small wardrobes have a lot to recommend them. A portable or capsule wardrobe simplifies our life and choices. We can simplify our lives by choosing a signature style and wearing it as a uniform. Perhaps just one style of t-shirt, or one style of dress. Or we may choose one colour and stick with that.

Care

It is commonly accepted that up to 25 per cent of the environmental footprint of garments comes from the way we care for them. We can reduce that footprint by caring for clothes in ways that also save us money and time. Only wash clothes when they are dirty or they smell! Preferably dry clothes on a clothes line not in a dryer. Get more life out of what you already own by paying attention and doing running repairs. If you feel a thread snap or notice a seam unravelling, attend to it immediately. As the old saying goes, a stitch in time saves nine. Revaluing the skills of mending does not only extend the life of clothing, it empowers us to create something uniquely individual. Mended garments carry a story of care. They reflect the triumph of imperfection over pretension, while the act of mending itself brings transformation in both mender and mended. By embracing repair as a valid and useful act, we (the menders) are stitching new life-energy into something others may throw away. When we pause and add a mark of care to our clothes, we extend their life and bring meaning to our own.

Make

Until we make something for ourselves to wear, we cannot appreciate the resources, time and skill that go into the clothes we buy. The fashion industry has conditioned us to be passive consumers. Everyone can buy clothes (with requisite cash or a credit card) yet few know the satisfaction of making something for themselves to wear. Sewing—or learning to sew—enables us to create something uniquely ours; reflecting our style and personality, independence and creativity. Making things makes us feel good. I’m not advocating we sew all our clothes. Rather, that sewing clothes is part of a growing ‘maker culture’ (think brewing, baking, preserving) because of the satisfaction of doing things for ourselves. It may even have measurable mental health benefits because working with our hands, head and heart can:

- relieve stress and anxiety

- generate a sense of pride and productivity

- enable autonomy and creative choices and

- boost brain power through concentration and problem-solving

Revive

Clothing has always been borrowed, exchanged and swapped, through both formal and informal networks. In a climate-changed world, we now have even more reason to embrace clothing revival as a winning strategy. There is no use-by date on simple, natural, well-made clothes. We can wear them until they wear out. Garments can have second, third, fourth and fifth lifetimes if we keep them in circulation. Landfill is a place of last resort. Secondhand is organic because when we buy pre-loved clothes, we do not add chemicals or production stress to the environment. Everything else is various shades of greenwashing. An additional benefit of wearing pre-loved clothes is reduced stress. You don’t have to worry about your clothes so much since you haven’t invested a fortune in them. Some of the benefits of wearing thrifted clothes are:

- The garments you purchase have inherent ethical and sustainable values, regardless of their origin

- You don’t extract virgin resources from Earth and are part of the solution by reusing existing ones

- It is a great way to experiment with your style by trying colours and shapes not available as ‘new’

- You never feel under pressure to make a purchase and can inspect garments at your leisure

- Older garments are often better-made than new ones, and chemical residues already washed out

- The money you save by not buying new can be deployed to holidays or supporting those in need

- Spending money in local op shops supports the good work of charities in communities

Adapt

The most creative and playful way to survive and thrive in a material world is to adapt existing clothes to suit yourself—upcycle garments already in circulation to create something new from old. Most people get the message about consumption overload, yet few personally invest energy and time in turning the tide. When we do, the results reflect our true selves and provide ultimate satisfaction. Taking time to redesign and refashion, to slice and dice unworn garments, then collage and stitch them together into a new form, creates something unique in the world. Upcycling is a way to revive home sewing in the 21st century. Sewing becomes empowering and ethical. Instead of sewing from scratch, existing resources can be recreated to suit yourself and reduce waste. Anything old can be new again when we have the skills and willingness to invest the time. Indeed, think of fibre and clothing as material resources and focus on refreshing, reusing and recycling—doing good for ourselves and the environment.

Salvage

There are endless opportunities to repurpose cloth when we turn our minds to it. Cleaning cloths: There’s something quite lovely about seeing a favourite old sheet or garment turn up in your cleaning rags. Memories resurface of what that piece of cloth used to be. Compost: When natural-fibre garments wear out, they effectively biodegrade and return organic matter to the soil. Be aware the thread in the seams will generally be polyester, so you may want to cut this away before adding the cloth to the compost or using it as groundcover under bark mulch. Handmade eco-products: Old clothes and linen can be upcycled into an endless array of accessories and homewares, dog toys, quilts, rag rugs, bunting, bags and wall hangings.

CHANGE TAKES TIME

Slow Clothing is an evolutionary concept and a journey of stepping back from the high consumption treadmill. It is about creating and wearing your own style, and ensuring it doesn’t cost the Earth. It is empowering to become more self-sufficient and independent. Before buying anything new, revisit what is already available and see what can be done to make it work better for you.

Slow Clothing is part of emergent thinking around revaluing material things, as articulated by economist Richard Denniss (2017) in Curing Affluenza: How to buy less stuff and save the world. Similarly, it taps into the return to a making and repairing culture documented by Katherine Wilson in Tinkering: Australians reinvent DIY culture. I’ve shared with many the simple pleasure of tinkering with our clothes to make them last longer and negate the need for buying more. This tinkering develops our curiosity and creativity as it builds resilience and independence from the earn more to spend more consumer cycle.

Embrace imperfection. Being perfect is impossible to maintain. Dysfunctional or discarded clothes provide opportunities for experimentation and learning new skills in ways that cost little. The potential for upcycling is endless, limited only by imagination, and available time and skills. Remember that Slow Clothing is about individual expression and personal connection to what we wear. We stitch to make a mark and be mindful. We are original, natural and resourceful.

[1] McKinsey report by Remy, N., Speelman, E. & Swartz, S. (2016). Style that’s sustainable: A new fast-fashion formula. Retrieved 17 November 2017 from http://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/sustainability-and-resource-productivity/our-insights/style-thats-sustainable-a-new-fast-fashion-formula?cid=sustainability-eml-alt-mip-mck-oth-1610

[2] Innovation in Textiles. (2017). Automated Sewbot to make 800,000 adidas T-shirts daily. Retrieved 17 November 2017 from http://www.innovationintextiles.com/automated-sewbot-to-make-800000-adidas-tshirts-daily/?sthash.hakeXKPj.mjjo

[3] Browne, M. (2011). Accumulation of microplastic on shorelines worldwide: Sources and sinks. Environmental Science and Technology, 45 (21), 9175–9179.

[4] Tyree, C. & Morrison, D. (nd). Plastics: The invisible inside us. Retrieved 17 November 2017 from https://orbmedia.org/stories/Invisibles_plastics

[5] Callewaert, C., De Maeseneire, E., Kerckhof, F., Verliefde, A., Van de Wiele, T. & Boon, N. (2014). Microbial odor profile of polyester and cotton clothes after a fitness session. Applied and Environmental Biology, 80(21), 6611–6619. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01422-14. Retrieved 17 November 2017 from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4249026/#B10