At Textile Beat, we love natural, simple, handmade things that don’t cost the Earth. We are endlessly refining the message about mindful, thoughtful ways of dressing that align with our values of authenticity and individuality. In the same way we endlessly upcycle our clothes, here’s the latest version of our slow clothing manifesto!

Slow Clothing culture

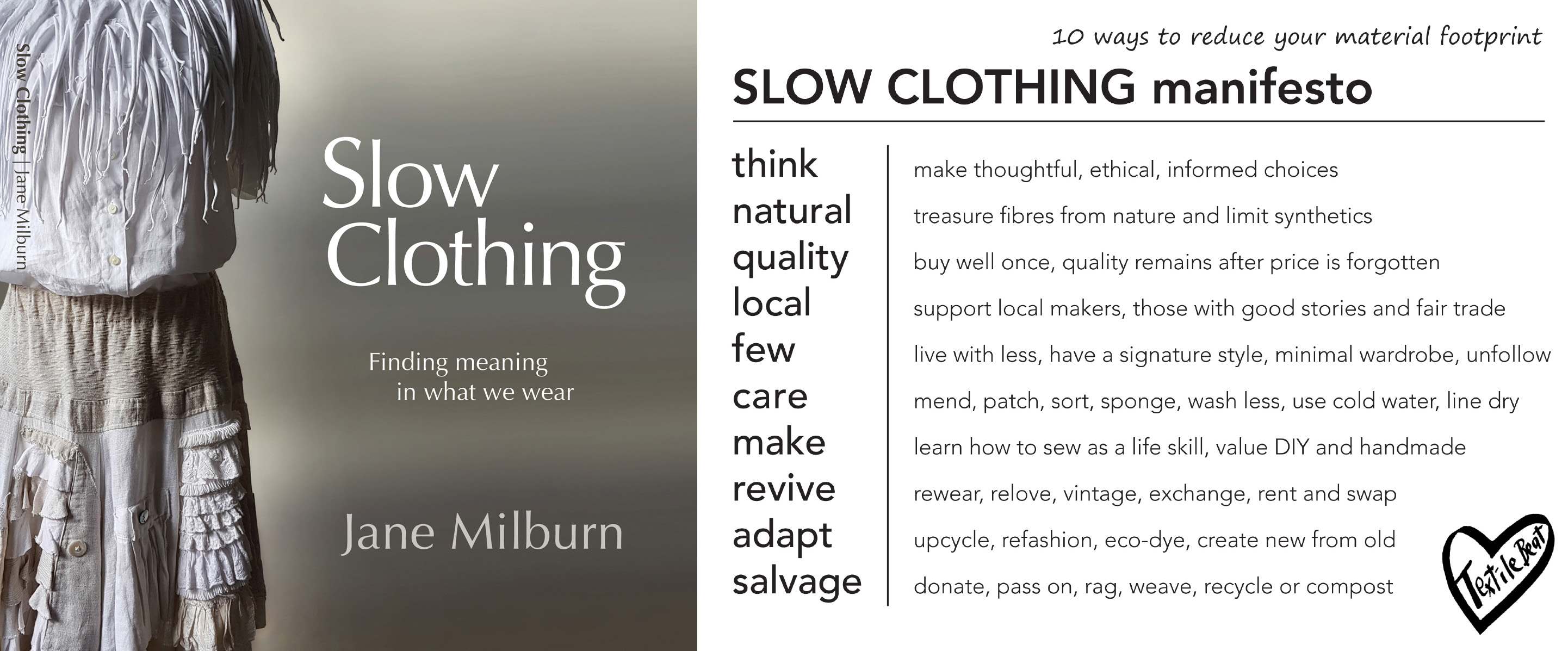

Slow Clothing is the antithesis of fast fashion. It is a way of thinking about, choosing, and wearing clothes so they bring value, meaning and joy to every day. We have finite resources on Earth and careful use of those resources is required to sustain our individual and collective future. Slow Clothing is a holistic approach to dressing that enables self-empowerment and individual actions to enjoy clothes while minimising our material footprint. It manifests through ten simple actions and choices—think, natural, quality, local, few, care, make, revive, adapt and salvage. This post is an extract from Jane Milburn’s 2017 book Slow Clothing: finding meaning in what we wear.

Dressing is an everyday practice that defines and reflects our values. We are naturally attached to clothes on a physical, emotional, even spiritual level. We are particular about what we wear because we want to look good, feel comfortable, reflect an image and belong. Yet almost all our garments are now designed for us and we choose from ready-made options based on our age and stage of life, work, status and spending capacity. Unless we deliberately choose to step off the fast-fashion treadmill, we are trapped in a vortex with little thought beyond the next new outfit—without consideration for how we can engage our own creative expression, energy and skills.

Dressing is an everyday practice that defines and reflects our values. We are naturally attached to clothes on a physical, emotional, even spiritual level. We are particular about what we wear because we want to look good, feel comfortable, reflect an image and belong. Yet almost all our garments are now designed for us and we choose from ready-made options based on our age and stage of life, work, status and spending capacity. Unless we deliberately choose to step off the fast-fashion treadmill, we are trapped in a vortex with little thought beyond the next new outfit—without consideration for how we can engage our own creative expression, energy and skills.

Investigating slow clothing culture

We live in a throwaway society, with an increasing amount of textiles used in the fashion industry made from synthetic fibres and garments produced using underpaid labour. Jane Milburn has a passion for natural fibres and believes behaviour change is needed towards dressing more responsibly, wearing clothes for longer and limiting the amount of textile waste thrown into landfill each year.

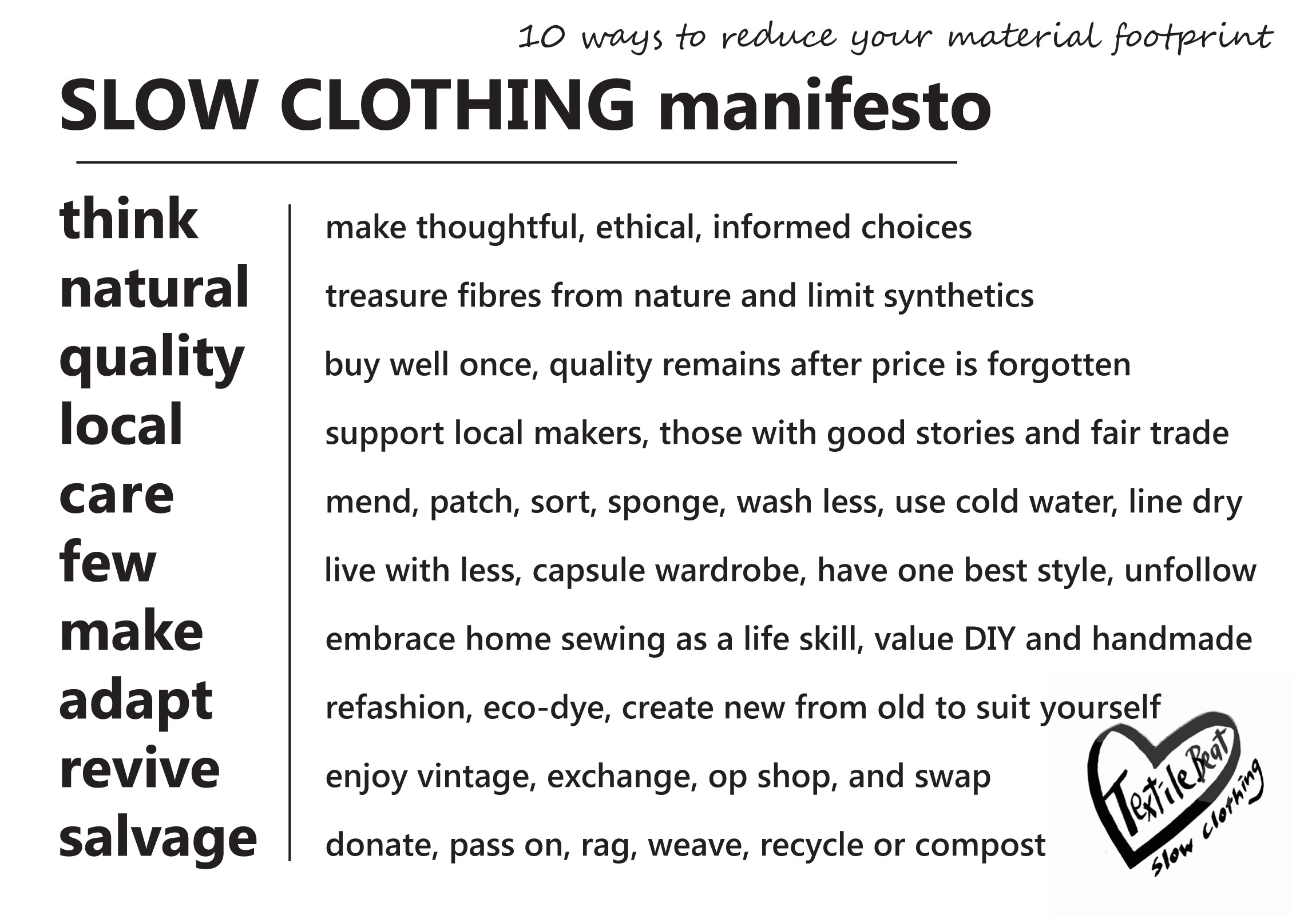

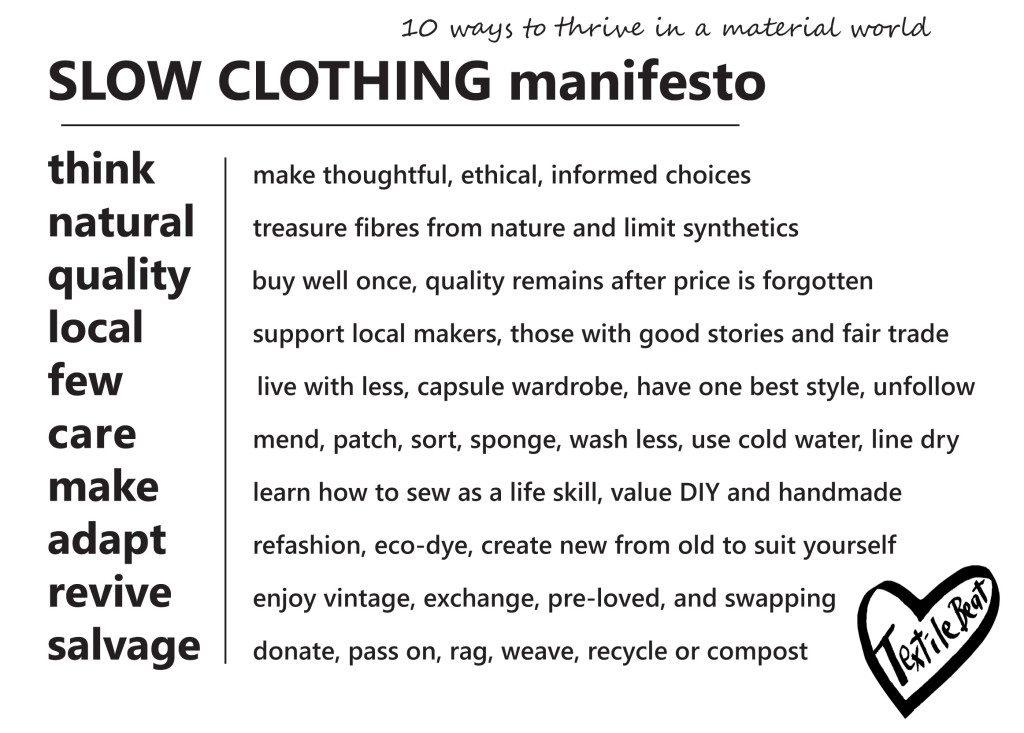

Using her campaigning and making skills, Jane created Textile Beat in 2013 and developed a 10-point Slow Clothing Manifesto of ways to reduce our material footprint. During the past six years, Jane has advocated for change across Australia through more than 560 engagements.

Wear change, do clothing slow

One million species are at risk and we humans are largely to blame, according to the latest UN biodiversity report. Governments, business and individuals need to act because we are eroding the very foundations of our economies, livelihoods, food security, health and quality of life worldwide, said Sir Robert Watson, chair of the UN’s Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services.

We can agitate for governments and business to take action – AND take action ourselves through the everyday choices in what we eat and what we wear. I wrote this Slow Clothing Manifesto back in 2015 to summarise the actions and choices we can take to reduce our material footprint: think, natural, local, quality, few, care, make, revive, adapt, salvage.

It becomes more relevant each year, with each new report on the need for transformative change. The power is in everyone, through everyday choices, to change the culture of consumption to one of conservation. Use what already exists, don’t feel pressured to buy more new, think bigger than yourself.

Slow Clothing book launches

Slow Clothing: finding meaning in what we wear presents a compelling case for wearers to change the way we dress and encapsulates a philosophy that is the antithesis of fast fashion.

Based on Jane Milburn’s five-year journey into natural fibres and upcycling, the book was launched recently in Sydney by ABC-TV’s War on Waste crusader Craig Reucassel and in Brisbane by ABC broadcaster Rebecca Levingston.

Rethinking clothing culture

By Jane Milburn Textile Beat founder and sustainability consultant

Textile Beat founder Jane Milburn clothed in wool garments given a second life using eco-dye. Photo by Ele Cook

My campaign on clothing waste has been a lifetime in the making. It began as a child learning hand-making skills and continued as a student upcycling big old dresses and thrifted finds.

I made many of my clothes for decades then rediscovered op shops in 2011 after a Fashion for Flood fundraiser. I began visiting op shops and particularly seeking out natural-fibre garments – wool jumpers with a hole, linen shirts with a missing button. The waste of resources troubled me because I grew up on a farm and have an agricultural science degree. What was happening to our clothing culture I wondered?

Slow Clothing at TEDxQUT

Below is original script from Jane Milburn’s TEDxQUT talk on April 8, 2017.

Below is original script from Jane Milburn’s TEDxQUT talk on April 8, 2017.

This suitcase weighs 23kgs – it’s overweight if you’re flying. And it represents the amount of leather and textiles that each Australian sends to landfill every year.

Every one of us … every year.

We know about food waste and that a third of food is never eaten – clothing waste runs parallel to that.

Every day we eat and dress to survive and thrive.

Our clothes do for us on the outside what food does inside. They warm and protect our body – and influence the way we feel. Continue Reading →

Slow clothing philosophy

Start where you are, use what you have, do what you can. Using observation and instinct, Jane Milburn and Textile Beat join the dots and explore a science-based narrative about clothing.

Clothes do for us on the outside what food does on the inside – they nourish and warm our body and soul. In the same way that conscious eaters are sourcing fresh whole food and returning to the kitchen, conscious dressers are seeking to know more about the provenance and ethics of clothing and curious about how it is made. Every day we eat and we dress to survive and thrive, and it is not just the style that matters, substance does too.

Fast and processed industrial food has had a dramatic impact on our health in recent years and similarly there has been transformational shift to industrial factory-made clothing, the social and environmental impacts of which we are only now coming to understand.

The Food and Agriculture Organisation reports that at least one-third of food produced is never eaten and creative solutions are emerging to divert and reduce that waste. In the same way, there is growing evidence a third of clothing is wasted, with much potential to upcycle and redeploy it. My purposeful work is bringing awareness to these and other material issues.

More than 90 percent of garments sold in Australia are now made overseas, mostly in Asian factories. Most people buy off-the-rack or online, with very few making anything for themselves to wear. As a natural-fibre champion, I am troubled that synthetic fibres made from petroleum now dominate the clothing market at a time when research shows these plastic clothes are shedding millions of microplastic particles into the ecosystem with every wash.

Engage in slow clothing

There is a huge excess of clothing in society due to the transformational shift in the way we buy, use and dispose of our garments these days, which is leaving us less engaged and wasteful.

We are buying up to four times more clothes than we did two decades ago, exploiting people and resources as well as creating environmental problems because of the trend towards synthetic clothes derived from petroleum.

We need to think more about whether we need new clothing, then choose to buy quality, natural, local and just a few.

Alternatively, we can get creative and learn to care, repair, adapt and revive existing clothing.

The Slow Clothing Manifesto is a summary of ways to thrive in a material world. Be more conscious about our clothing, in the same way we have become conscious of our food.

More clothing, fewer skills

Australians buy an average of 27 kilograms worth of new clothing and textiles each year, two-thirds of which are made from manmade fibres derived from petroleum according to sustainability consultant Jane Milburn.

Ms Milburn said Australians are the second-largest consumers* of new textiles after north Americans who annually buy 37kg each, and ahead of Western Europeans at 22kg while consumption in Africa, the Middle East and India averages just 5 kg per person.

“There’s been a transformational shift in the way we source, use and discard our clothing which has major social and environmental implications. Fast fashion produced from global supply chains is driving excessive purchasing of affordable new clothing often discarded after a few wears,” she said.