During 2016, The Slow Clothing Project published 40 stories of people who make items of clothing for themselves to wear. It is fabulous to be able to conclude with a story from someone who has both personal and academic insights into our desire to make and create.

After five years of research into creativity and DIY, and many years of ‘hands on’ engagement with design-build projects, Dr Nicola Dawn Smith from Yallingup in Western Australia said her experience indicates the enormous personal and environmental value in becoming a bricoleur.

Dr Nicola Smith wears her comforable and buttonless top made in her style for The Slow Clothing Project.

“A bricoleur (as interpreted in my study) is someone who uses whatever is to hand (not buying more tools/materials) with whatever skills they have (and can learn); someone who becomes immersed in the moment, the practice, the doing,” Nicola said.

“From interviewing over 30 DIYers about home life, I found people’s choices gravitated towards long-term comfort; in houses, in social situations, in furniture, in food, and on a daily basis in clothes and shoes as casual wear – the favourite old jeans, the faded T-shirt.

“By contrast, fashion (driven by greed, fear of being left behind/out, etc) only provides very short-term comfort; the transient nature of novelty and newness then is perhaps the root of all evil when it comes to the ‘stuff’ acquired as a temporary fix (clothes, furniture, home interiors, cars).

“Novelty and the need to possess at the expense of creativity (doing), longevity and comfort has a lot to do with why so much clothing and home furnishing gets discarded – it is appealing on the hanger/in the display, but ultimately does not feel quite right next time it is worn, not comfortable, not appropriate, not in character.

“While there are movements like LOHAS, LOVOS and PARKOS encouraging people to question fundamental life priorities and values, many aspects of ‘sustainable living’ are being used to drive yet more consumerism – organic food and clothing, ecotourism, even recycling.”

As a designer herself, Nicola has always been interested in aesthetically pleasing objects/spaces/clothes/shoes, yet never been quite able to justify the consumption of items that feel like a ‘want’ rather than a ‘need’.

“Perhaps from childhood, or from early days as a student, acquiring something new always came with a sense of guilt, and the more superficial it was to the core needs (think Maslow’s triangle), the more shallow the experience. While at university, money was scarce and we were inventive – why buy new when recycled, salvaged or second-hand would do?” she said.

“The first time living in a developing country reinforced my appreciation for something hand-made with care over something carelessly mass-produced. I worked in Nigeria many years ago for a design-build company and clearly remember the sharp contrast between worlds when I returned to the UK; the locals were incredibly resourceful with so little, finding ways to utilise things discarded by others.

“Decades later, my work as a design consultant has taken me overseas on many occasions, mostly to China and Hong Kong where our urban design projects were typically vast residential and commercial developments. The insatiable demand for housing, goods and services in China driven by a growing middle-income sector of the population, ambitious and seeking the ‘Western way of life’ – in other words, a life of consumption.

“Over time as I started lecturing in design and architecture, I became interested in this notion of a ‘Western way of life’, specifically the concept of ‘lifestyle’, and how the ‘dream lifestyle’ is engineered or designed – fuelled by and fuelling consumption.

“As a doctoral thesis topic, I researched how both professionals and DIYers set about improving their homes in the hope of living a better life, having the ‘perfect’ lifestyle. I looked at the influence of the media on home improvement (including Grand Designs), the influence of consumption on homeowners (the rise and rise of Bunnings), and the pressure to have a dream home and a perfect way of life.

“During the research it became clear that most people are locked in a daily struggle between wants and needs, resources and desires, creativity and consumption, and between real and imagined lives. I also observed a significant difference between the way professional designers imagine and realise home improvements, and the process taken by those who simply want to ‘have a go’. While just about everyone found value in the DIY activity, the planning and doing rather than the outcome, the non-professional designers were less constrained by their knowledge of ‘normal’ building design/build solutions and seemed to be more free to experiment, improvise, appropriate, re-use materials to hand and were more willing to collaborate.

“The most valued DIY experiences were reported by those who had lifestyles of simplicity and practicality, of collaboration with others (family, friends), of constant creative challenges. The least satisfied were those driven by continual consumption, motivated by the resale market, the fear of being left behind.“

Nicola said the research findings also suggest that in taking personal control over your immediate environment and shaping the way you live, people are able to feel confident, competent and capable. The seemingly autotelic nature of DIY may provide an opportunity for self-growth and the capacity for embracing change.

As she reflects on the influences that shaped her career and lifestyle, Nicola can now see that design, creativity, craft, DIY and ‘hands on’ landscape have been there since childhood.

“I grew up in one of the few garden villages in the United Kingdom emerging from Ebenezer Howard’s Garden City Movement. The vision for the village centred on a strong sense of community and self-sufficiency, and at the little village school we were encouraged to try everything regardless of gender – cookery, woodwork, metalwork, knitting and of course sewing – by hand and on Berninas,” she said.

“At home my brother and I were always hands on, helping hang wallpaper, edging lawns, contributing to the Sunday bake (with an eye on licking the bowl clean no doubt). Generations of women in the family and neighbourhood regularly sewed, embroidered, knitted and crocheted, mostly out of necessity in post-war England; making clothes from curtains, unravelling woollen garments and re-using the wool, turning collars.

“My earliest memories of machine sewing were on an old black Frister and Rossman on the dining room table, trying to dismember a skirt made of a pretty print (yellow daisies on white background – I can still picture it) horribly contaminated by buttons. Confession: I have a passion for patterns but a phobia for buttons (koumpounophobia) that has very much steered my wardrobe and dressmaking choices since about age five! You would not believe how many things made of lovely fabric have buttons on!

“I blame it all on my grandmother’s button tin. It was a large rusty old shortbread tin (although much of the print had long since worn off) seething with grimy buttons – small pearl ones, brass uniform ones, large coloured plastic ones, odd shaped metal ones with bits of thread still on, baby ones shaped like ducks and dogs – and grit that got right under your nails. Cardigans and blouses were the most reviled of garments (and still are), simple shift dresses (possibly with zips), jeans and T-shirts the most adored (and still are).

“With a button phobia, early on I gravitated to rather plain loose-fitting clothing rather than the formal and frilly. Like many growing up in the ‘70s, my wardrobe comprised simple basics – jeans and T-shirts, skirts and polo neck jumpers. One of the early school projects was a three-tier ‘peasant’ skirt with zip/hook and eye fastening. Supposedly worn with a longer petticoat underneath (lace showing) it was definitely not ‘me’ even though I loved the fabric and ultimately cut it up later for another project.

“Over the years, I have tried to address the gulf between creativity and ability, my technical skills flagging far behind; pattern-making classes, fashion courses, print-making, re-fashion/re-cycle workshops, informal sewing groups and reading books and blogs. Although I always enjoyed the process, there were clear limitations to what I was able to produce,” she said.

The Slow Clothing Project provided a reason for Nicola to revisit her fabric stash and more op shops, and create a series of tops in keeping with her relaxed country style.

“I found some flat cotton sheets in soft well-washed colours in the local church op shop and picked out a few patterns to trial. Unusually patient, I made a couple up from old white sheets initially to see how well the sizes fitted, if the dresses could work shortened to tops, and get familiar with the instructions. Once the rough mock-ups seemed okay, a couple of sheets went for the chop – orienting the paper patterns to incorporate the broad top/pillow end hem.

“I soon discovered this caused problems with the side seams and added pockets over the dubious junctions! Unpacking a couple of cartons from relocating four years ago, I found some old IKEA curtains and table runners. Even though we have 60 windows, we have no need for curtains in our new place, so I used the fabric to make a larger top size as it made the heavier fabric more comfy to wear.

“I soon discovered this caused problems with the side seams and added pockets over the dubious junctions! Unpacking a couple of cartons from relocating four years ago, I found some old IKEA curtains and table runners. Even though we have 60 windows, we have no need for curtains in our new place, so I used the fabric to make a larger top size as it made the heavier fabric more comfy to wear.

“The frequency of wear is the gold standard test of a garment’s success for me. If it is not comfortable, practical (cool or warm and loose) or presentable, it doesn’t get its day in the sun and most likely it goes back in the re-making pile!”

“What I created is now my absolutely most favourite top – simple, practical, comfortable, soft (no doubt from years in the wash and blowing on a line), lightweight and worn all the time with shorts/jeans/capri pants – I love the shape and the fabric (and of course no buttons!).

These photos of Nicola’s creations show glimpses of the prototype house she and partner John are building near Yallingup in the Margaret River Region of Western Australia – in every way a ‘slow’ build project.

“We found an open block of land previously part of a farmstead; rather than clear woodland and wildlife habitat in order to build, we wanted to add ecological value to a block which had been cleared for decades. We also started collecting jarrah (local hardwood) from salvage yards and stockpiling on site ready to de-nail and machine ourselves,” Nicola said.

“We had already renovated a number of properties and found conventional houses too restrictive for our constantly changing patterns of living. We tried to focus on abstract notions such as value, experience and interpretation (of issues such as comfort) rather than access, circulation and storage, although these came to the fore as the plan materialised.

“A courtyard with water feature (think Moorish gardens) forms the nucleus of the house, bounded on three sides by open wings acting as interchangeable living, sleeping and work spaces. The house had to meet 6-star ratings, so is solar-passive, double-glazed and well-insulated. New technologies have been embraced wherever they add to the environmentally friendly operation of the property, such as the aerobic wastewater system.

“With limited resources (time and money), an industrial-style of build allowed us to do most of the work ourselves without the need for finishing trades. Importantly the building was to be an open canvas, allowed to evolve during construction (something typical construction projects avoid due to cost) as well as after we moved in.

“One wing of the building was always allocated as guest space for friends and family, but overtime interest in the build style and ethos encouraged us to open the ‘guest wing’ as short stay accommodation. Our visitors are mostly attracted to the design of the property, the features and furnishings (all made/repurposed on the property) and the concept of ‘simple living’. The build has been documented here and the guest wing here.

In conclusion, we return to the slow-clothing theme and Nicola’s advice for someone starting out on a making journey: “Do not be too critical of your skills and imagination; it leads to procrastination. If you buy pre-loved clothing or sheets to experiment with, you are supporting a charity, keeping resources in a cycle of use for longer and not fuelling consumption. You are also keeping your own costs to a minimum which will help you feel less fearful of ‘ruining’ something and ‘wasting’ your money – a win/win. With pre-made garments and linen you will have something interesting to work with (seams, edges, buckles, buttons – agh!!!) because there is nothing harder or more intimidating than designing with a clean slate, a flat length of new cloth.”

Nicola believes the evolution of ideas, like garments, takes time. The most satisfying and successful projects seem to emerge from a melting pot of influences and interests, needs and want, constraints and opportunities, all given the proper time to evolve.

Fabulous, thanks Nicola for interpreting this year-long journey into slow clothing, as experienced by makers and creators from around Australia. Our stories (linked here) show the range of approaches people take to making something for themselves to wear. The connection between the stories is in being resourceful, creative, thoughtful and individual – and gaining immense satisfaction from skills honed in the making process.

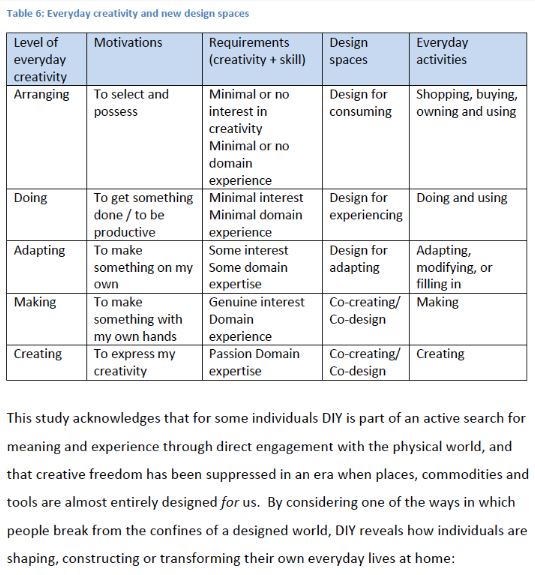

This summary table, below, from Nicola’s PhD outlines the shades of DIY creativity.