Clothes are made from three fibre types – synthetic fibres, reconstituted cellulose fibres and natural fibres – or blends of these.

Synthetic fibres – polyester, acrylic and nylon – are derived from petroleum and are a type of plastic. While cheap to produce synthetic fibres shed microplastic when washed, don’t breathe and research shows they are likely to harbour more bacteria and odour than natural fibres. Synthetics also gather static electricity and may cling to your body in uncomfortable and embarrassing ways.

Reconstituted cellulose fibres – such as viscose, rayon, bamboo, lyocell and tencel – while manmade are derived from plants and wood and therefore more natural then synthetics. They have design advantages, are comfortable to wear and easy care but there are concerns about chemicals used in their production.

Natural fibres – cotton, wool and linen – tend to be more expensive and water-intensive to produce, therefore we should treasure them until they wear out. Cotton is the dominant natural fibre. Seek out sustainable and organic cotton where you can. Linen is one of the greenest fibres but often out of favour because it wrinkles (wash, shake, hang to dry and wear without ironing). Hemp is less readily available, but equally as green as linen (if not more so). Animal fibres like wool, alpaca, cashmere and silk are expensive and need a little extra care but will last a long time and wear well between washes.

Fibre issues

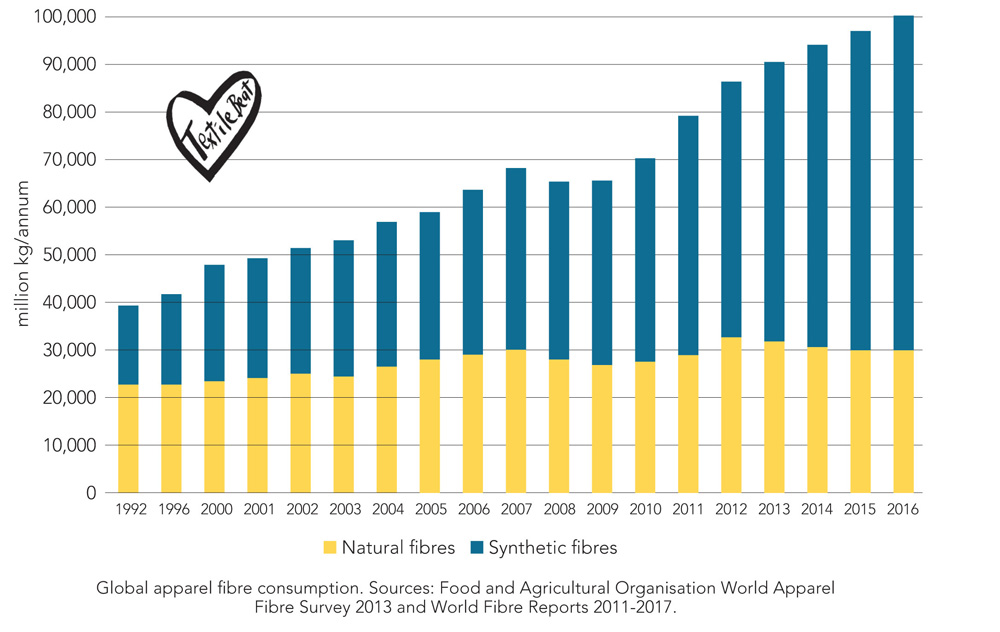

In earlier times, clothing was relatively scarce and made from natural fibres. In about the 1930s, the arrival of synthetics like polyester and acrylic, derived from petroleum, provided cheaper alternatives for a growing global population. By the year 2000, synthetic fibres filled half the market need and now synthetic represent two-thirds of new clothing and textiles – far surpassing natural fibres (see graph above).

Synthetic fibres are plastic

A big problem with synthetic fibres is they are plastic. Synthetic clothes, being essentially plastic, may never break down in the environment or buried in the anaerobic conditions of landfill.

As part of global research looking at shoreline pollution, ecologist Dr Mark Browne found synthetic clothing sheds microplastic particles (<1mm) which eventually flush into oceans to contaminate the food chain and the planet. Browne said ingested and inhaled fibres carried toxic materials: that up to one-third of the food we eat is contaminated with this material. The study published in Environmental Science and Technology, found:

Experiments sampling wastewater from domestic washing machines demonstrated that a single garment can produce >1900 fibres per wash. This suggests that a large proportion of microplastic fibres found in the marine environment may be derived from sewage as a consequence of washing of clothes. As the human population grows and people use more synthetic textiles, contamination of habitats and animals by microplastic is likely to increase.

A Primary microplastics in the oceans report , prepared by the International Union of Concern for Nature, found almost all microplastic in the oceans came from land-based activities, with the laundering of synthetic textiles said to be a key source. Further disturbing new research has found microplastic present in the majority of our drinking water. Scientists indicate the most likely source to be the everyday abrasion of synthetic clothes, upholstery, and carpets.

Natural fibres use land, water and energy

There is increasing competition for agricultural land and water from the world’s expanding population and urban sprawl. While natural fibres do have an environmental cost in the production phase – using land, water, nutrients, energy and chemicals – the fibres are biodegradable. In terms of water use, United Kingdom sustainability group WRAP (2012) said the cotton used to make a pair of jeans required about 10,000 litres of water to grow, while other groups have said it takes 2720 litres of water to make a t-shirt – as much as one person drinks over a three-year period. Although dwarfed by the United States, China and India in terms of production volume, the Australian cotton industry has made serious strides in improving its sustainability credentials since 1997 through the introduction of a Best Management Practice program which includes environmental auditing and water-use efficiency measures. Adoption of integrated pest management systems and cotton plants modified to resist insect pests have enabled significant reduction in pesticide use, down by 90 per cent. Improved water management has seen water use reduced by 40 per cent. Only two per cent of the world’s cotton is grown organically, in high-altitude parts of Texas in the United States, India, China and Turkey. Organic materials are certified by the Global Organic Textile Standard (GOTS).

Cotton and linen are plant fibres (cotton from flowers, linen from flax leaves) while wool is a protein fibre from sheep fleece. All three have much less embodied energy than synthetics. Cashmere, alpaca, mohair and silk are specialist protein fibres are only produced in small quantities.

Reconstituted fibres use chemicals and resources

Viscose, bamboo, lyocell and modal are manmade from reconstituted plant fibres. They have merit but are produced by a chemical process using potentially hazardous caustic soda (sodium hydroxide) and carbon disulphide. The wood pulp used for lyocell and modal may come from endangered forests, adding further to its environmental burden. New cellulose fibres derived from industrial organic waste are in development and have promise.

While recycled polyester and plastic bottles reincarnated as synthetic fibres may have some social and environmental merit, they are not biodegradable and shed microplastic. Technology for separating and recycling blended fibres (such as poly cottons) is still being refined. Recycled cotton (which has short fibre length) needs to be blended with virgin cotton to be serviceable.

When you are buying clothes, check the label to see what they are made from and how to care for them. Useful resources include the Good on You app. These words extracted from Slow Clothing: finding meaning in what we wear by Jane Milburn. Ask if your library has a copy, or purchase a copy in Australia or overseas. More useful information about the environmental impact of clothing here.