Disruption arising from the pandemic reminds us of the need to live thoughtfully in tune with nature, as Jane Milburn reports.

Jane Milburn wears self-made upcycled silk dress. Photo by Robin McConchie at Mt Coot-tha Botanic Gardens.

Sewing arose as a survival skill during the COVID-19 pandemic when global supply chains fractured and locally-made cloth face masks became valuable personal protection equipment. Even New Zealand Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern made her own face covering to help stop the spread of the coronavirus when masks became mandatory on public transport during the Auckland breakout.

Around the globe, the accompanying stay-at-home orders meant the landscape of our lives changed overnight with days, weeks, sometimes months, of resurrecting DIY skills and making the best of what was at hand. For those not required at the front line, lockdown became a time of baking and gardening, sewing and mending, zooming and home-schooling. Online shopping boomed, but that’s another story.

United Kingdom Prime Minister Boris Johnson used a sewing analogy to describe his actions to prevent the virus spreading as ‘a stitch in time saves nine’, sparking University of British Columbia lecturer Mary Gale Smith to reflect on how the COVID-19 pandemic brought the practical uses of sewing and craft into the news.

Writing on The Conversation, Ms Smith said the pandemic sewing rush saw many sewists and crafters dusting off their sewing machines or purchasing new ones to sew masks for themselves and others, for frontline workers or for sale. She said that sometimes, buried in stories of pandemic sewing, was a comment that at one time such skills were typically taught in schools.

The practical home-based DIY skills and activities we rediscovered during lockdown proved to be not only useful, there are ecological and wellbeing benefits too.

The old stitch in time proverb sits alongside ‘mend and make do’, and ‘waste not want not’ as contemporary calls to action at this time of relative excess in a similar way that they did in response to scarcity during wartime and the Great Depression.

This is relevant because planetary health experts have labelled the pandemic as a wake-up call. People such as my brother Professor Anthony Capon, director of Monash Sustainable Development Institute, warn that the pandemic is a crisis of our own making and intrinsically linked to the climate and biodiversity crises.

Prof Capon says each crises arises from our seeming unwillingness to respect the interdependence between ourselves, other animal species and the natural world more generally.

In March last year on The Conversation, he and colleagues wrote that climate change is undermining human health in profound ways. It is a risk multiplier, exacerbating our vulnerability to a range of health threats.

They wrote: ‘The current COVID-19 pandemic is yet another warning shot of the consequences of ignoring these connections. If we are to constrain the emergence of new infections and future pandemics, we simply must cease our exploitation and degradation of the natural world, and urgently cut our carbon emissions.’

‘Controlling the pandemic appropriately focuses on mobilising human and financial resources to provide health care for patients and prevent human to human transmission. But it’s important we also invest in tackling the underlying causes of the problem through biodiversity conservation and stabilising the climate. This will help avoid the transmission of diseases from animals to humans in the first place.’

We know our health depends on healthy ecosystems and we need governments to step up to ensure public policies and development projects do not further compromise the natural world.

Concurrently, as individual stewards of the Earth with free will and capacity to make a difference, we can all create change for good. These ecological crises are interconnected with our everyday choices and actions in what we eat, what we wear and how we live.

One troubling aspect of what we wear continues to be the sheer volume of clothing we purchase. Its impact on the environment is likely worsening despite brands touting sustainability credentials and offering gimmicky takeback solutions.

In December 2020, a House of Representatives report From Rubbish to Resources: Building a Circular Economy by the Standing Committee on Industry, Innovation, Science and Resources reflected figures that I originally sourced and published on my Textile Beat website back in 2016.

They reported what I have been saying for some time: Each year, the average Australian purchases 27kg of clothing and disposes of 23kg to landfill, and that textile waste has the lowest recovery rate of all waste types with 87.5 per cent going to landfill.

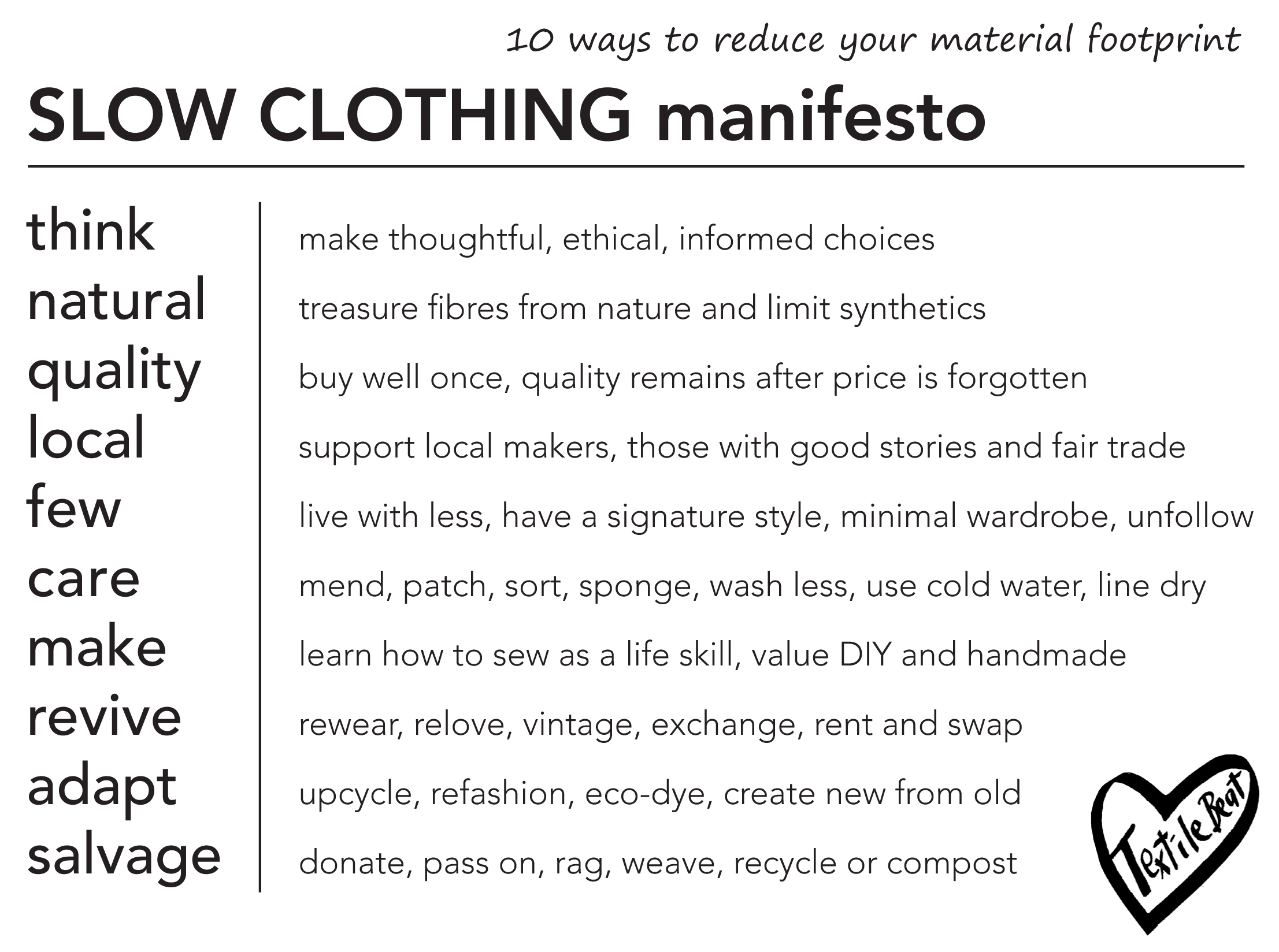

Our current clothing consumption is unsustainable and we can all taken sensible actions (think, natural, quality, local, few, care, make, revive, adapt and salvage) as outlined in 2015 in my Slow Clothing Manifesto. We can buy fewer clothes and wear them for longer. We can buy preloved, avoid synthetic fibres, wash clothes only when necessary, and act creatively in what happens to clothes when we no longer need them.

I believe in the power of adaptation in the natural world as well as our own ability to adapt clothes, behaviours and outcomes. This is what rising to resilience is about. It is our ability to recover from difficult circumstances, to find creative and resourceful ways to navigate change so it does not overwhelm us.

When the global pandemic deferred my Churchill Fellowship study tour, I adapted by initiating a Virtual Churchill and doing a Permaculture Design Course both of which affirmed my focus on natural fibres, self-reliance and regeneration.

Permaculture was developed in the 1970s by Australians Bill Mollison and David Holmgren and the principles of using slow and sustainable solutions, valuing renewable resources and services, applying self-regulation, creatively responding to change and producing no waste are particularly relevant at this time. We need to be always adapting and evolving, choosing ethical and mindful ways of living in a climate-changing world.

This builds on the 1960s pioneering environmental work by Rachel Carson in Silent Spring when she called on humans to act responsibly, carefully and as stewards of the living earth. Ms Carson identified human hubris and financial self-interest as the crux of the problem and called upon us to master ourselves and our appetites to live in harmony with nature.

This article first published in QCWA’s Ruth magazine Autumn edition