Do you carry an old-fashioned cloth handkerchief in your pocket or purse? Tissues and packaged wipes might be more convenient but we are becoming aware of their cumulative waste and moving back to reusable products.

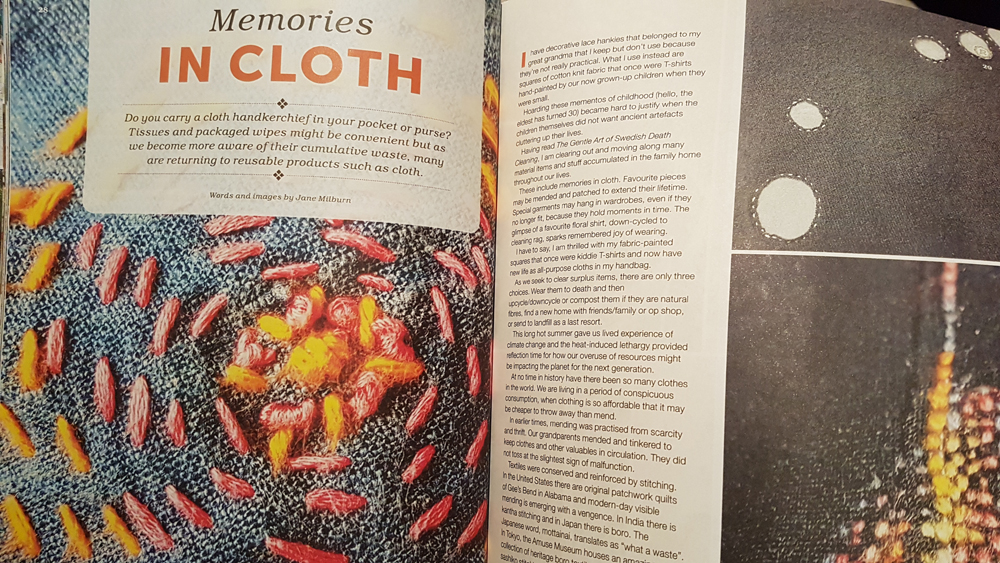

There are memories in cloth. Favourite pieces may be mended and patched to extend their lifetime. Special garments may hang in wardrobes, even if they no longer fit, because they hold moments in time. The glimpse of an old favourite floral shirt, down-cycled to cleaning rag, evocatively sparks remembered joy of wearing. I am thrilled with my fabric-painted hanky squares that once were my little kids t-shirts (they’re now aged 24, 29 and 30) now upcycled as all-purpose cloths in my handbag.

As we seek to clear surplus items from our homes, there are only three choices. Wear them to death and then upcycle/downcycle or compost them if they are natural fibres, find a new home with friends/family or opshop, or send to landfill as a last resort.

This long hot summer of 2018/2019 in Queensland gave us lived experience of climate change and the heat-induced lethargy provided reflection time for how our overuse of resources might be impacting the planet for the next generation.

At no time in history have there been so many clothes in the world. We are living in a period of conspicuous consumption, when clothing is so affordable that it may be cheaper to throw away than mend.

In earlier times, mending was practiced from scarcity and thrift. Our grandparents mended and tinkered to keep clothes and other valuables in circulation. They did not toss at the slightest sign of malfunction.

Textiles were conserved and reinforced by stitching. In the United States there are original patchwork quilts of Gee’s Bend in Alabama and modern-day visible mending is emerging with a vengence. In India there is kantha stitching and in Japan there is boro, The Japanese word, mottainai, translates as ‘what a waste’. In Tokyo, the Amuse Museum houses an amazing collection of heritage boro textiles renovated using sashiko stitching.

We’re catching on. Mending is trending. It is the simplest way to minimise our material footprint and an ethical and sustainable action within easy reach. It is something country people attuned to conserving resources have routinely done.

Mended garments carry a story of care and reflect the triumph of imperfection over pretention. Mending is fun, and good for the soul. It brings transformation in both mender and mended.

We could dispose of clothes with holes, stains or tears – or we can mend them to extend their useful life. Each moment of mending becomes an investment in the change we want to see. Our mending actions push back against endless consumption. When we mend, we embrace the imperfect reality of a mended life.

Mending also makes us feel good because the rhythmic movement of needle through cloth brings our mind into the moment. When we put energy into fixing clothes they carry our signature, be it neat or messy. These words are an extract from The Process of Mending zine available at textilebeat.com

Darning

Darning is a way to repair holes in fabric. Essentially, you need to replace the fabric by weaving new threads (a warp and a weft). Using knitting wool or another substantial thread, make long stitches across the hole (check tension to avoid puckering) then change to the opposite direction and weave in and out of these threads to fill the hole.

If you are darning a sock, avoid using knots by weaving the ends back on themselves. If the hole is very small, just make one stitch left to right and another top to bottom. Darning can be decorative using contrasting or multi-coloured threads to please your eye. Ensure you darn into the fabric beyond the physical hole, as it currently exists, to prevent future weaknesses. Stitching circles are another way to darn a small hole.

Patching

There is no limit as to what can be done with hand-stitching to repair and embellish garments. Use an old t-shirt or wool garment, denim or woven fabric to create your patches, which can then be applied from above, or below (cut away the top layer after you have attached the patch underneath). Use running/sashiko stitch and decorate with buttons or threads to your own style.

Caring for clothes is integral to slow clothing philosophy through which we choose to dress for health and wellbeing rather than status and looks. Slow clothing is an antidote to fast fashion based on everyday actions and choices, which I’ve written about in Slow Clothing: finding meaning in what we wear.

One last word on disposable items. Vanuatu has announced plans to be the first country in the world to ban disposable nappies due to environmental concerns. Brisbane City Council has flagged disposable nappies as its biggest landfill issue. When you consider the birth rate in Australia, over 3.6 million nappies are used every day or 1.3 billion nappies every year. Wonder how long we can keep burying this problem? Modern cloth nappies are the reusable option used by less than 5 percent of parents, making laundry not landfill.

This article first-published in Ruth Magazine Winter 2019 edition. Ruth Winter 2019 Memories in cloth