There is simply no precedent for the volume of clothes in the world today so we are experimenting with ways to keep material resources in local circulation through soil after its initial purpose is served. Soil is our biggest carbon sink and the source of all fresh food and natural fibre, so it truly has superpowers worthy of enriching.

The composting process cycles four of life’s building blocks – carbon, oxygen, hydrogen and nitrogen – back into the soil so that it can support new growth. The clothing fibres need to be moistened to encourage and speed the decomposition process. The fibre becomes food for microbes, bacteria, fungi, moulds, worms, beetles, snails, mites, cockroaches and other critters, which are all part of the process.

By all accounts, when food and clothing go to landfill they emit the greenhouse gas methane which contributes to climate change. We can compost food waste in our backyards and neighbourhoods, so why not our clothing waste? Of course clothing with wearable life can be donated to charities but composting is a solution for cloth that has exhausted other purposes.

I cannot find a textbook that discusses composting clothes to regenerate as organic matter but I did find this online reference. Industrial clothing recycling solutions may arise, but in the meantime composting provides a local solution.

In 2018, I did a backyard experiment and found most of the natural-fibre material swatches (wool, cotton, linen) disintegrated into ‘soil’ within the year while synthetic fibres remained inert. This is because fibres like polyester, nylon, acrylic are plastic, derived from fossil fuels the same as plastic bags, containers and bottles.

This year, we did another experiment with six garments (all started of similar size/volume) made from different fabric types being buried for three months in a compost bin at Bulimba Creek Catchment Sustainability Centre at Carindale in Brisbane.

Jane Milburn and Bulimba Creek Catchment Sustainability Centre nursery manager Leigh Weakley bury clothes in late May, left, and dig up in late August 2019.

Five of the garments were natural fibres (wool, cotton, linen, silk, viscose-blend) the sixth was lycra (not expected to breakdown). Most of the thread used to sew garments is polyester (synthetic) so it is not likely to breakdown. Buttons were reclaimed before burial.

We found the wool, cotton and viscose garments decomposed into organic matter quicker than linen and silk. All had decayed to some extent, but the surprise was the silk (protein fibre, slower to breakdown than cellulose/plant fibre) which although it showed signs of erosion was largely intact after the three months. The lycra just looked like it needs a wash after a hard night. We could also clearly see the polyester stitching on cotton garment and the poly/elastaine webbing in the viscose blend garment which remained largely intact.

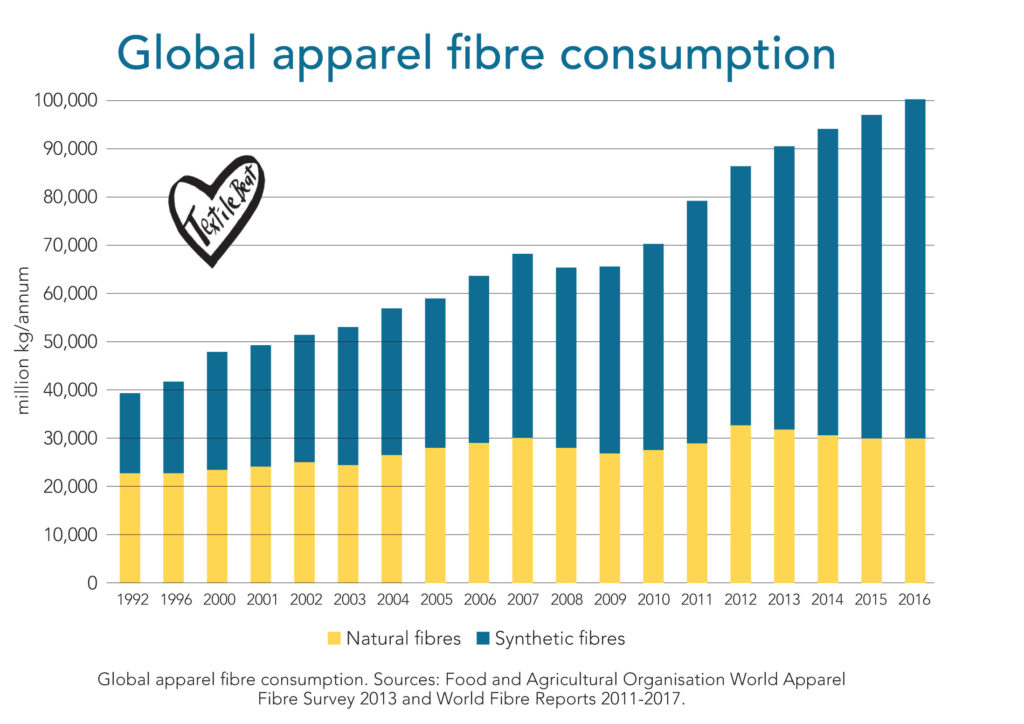

The message is: Natural fibres are regenerative, they return nutrients and organic matter to the soil. Synthetic fibres are plastic and never breakdown. Did you know 2/3 of clothing (see graph below, from Slow Clothing) are made from synthetic fibres, derived from petroleum, and shedding microplastic particles with washing and wearing? Bit of a problem that. The practical response is to buy fewer new clothes, choose natural fibres and wear them until they wear out. Through Textile Beat, we’ve been running these lines since 2013 and it is affirming to see them arising in many different channels.